E-Museum of Pyrographic ArtAntique Pyrography Tools Exhibit

|

|

| PATTY THUM

Adapted from Southern Magazine, 1894, p. 62. |

|

|

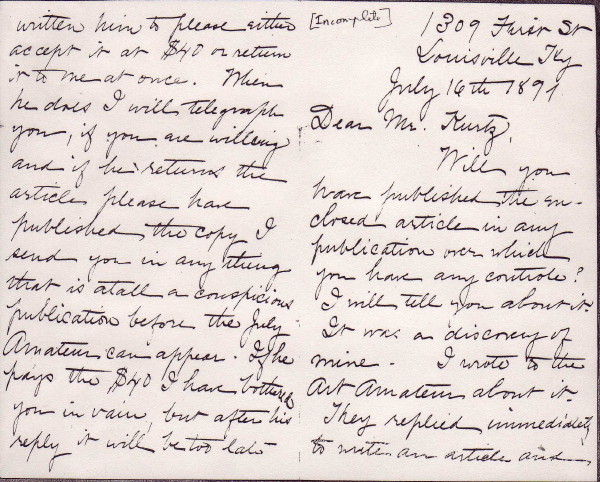

Letter (partial). View of two of seven pages, dated July 1891, of Patty Thum's letter to Charles Kurtz that included a 15-page enclosure of the draft text for an article with the subject "Burnt Wood Work." It recounted her personal discovery of pyrography ("fire drawing") as an art form and her astonishing invention of an electric pyrography tool.

Digital image from microfilm reel 4810 of the Charles M. Kurtz papers in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, National Portrait Gallery Library, Washington, D.C. N.B. The first page had the parenthetical "[Incomplete]" written at the top; however, two stray pages found elsewhere in that same reel (4810) seemed precisely the missing ones to complete Patty Thum's letter. |

Since the original discovery of Patty Thum's 1894 illustrated letter to the editor of Art Interchange, introduced here in the E-Museum, an earlier letter—handwritten in July of 1891— has turned up in the (microfilm) archives of the Smithsonian Museum's Library in Washington, D.C.

In her recently discovered 1891 letter, exhibited here, you will see that Patty Thum mentions "Mandeville" in regard to her electric tool. Mandeville Thum was her brother and a physician. He was the one who introduced her to the electric cautery tool, which was at that time the latest medical technology that was beginning to replace the thermo-cautery tool that had been invented in 1875 by a Dr. Claude Pacquelin in France.

It was somewhat AFTER Patty Thum's 1891 letter that J. William Fosdick was talking about his thermo-pyrography tool for the first time. His pyrography tool was likewise an adaptation, invented (not by him but by François Manuel-Perier***) from a surgical cautery tool (viz., Dr. Pacquelin's thermo-cautery tool).

Manuel-Perier demonstrated his invention of the thermo-pyrography tool at the 1889 International Exposition in Paris. However, it is important to note that J. Wm. Fosdick discontinued his studies and left Paris in 1888 to begin his career in New York City. When he wrote his 1891 article, he apparently was not yet using the thermo-pyrography tool, as he made no mention of it there.

It wasn't until February 1892 that J. Wm. Fosdick was talking about his thermo-pyrography tool in an interview with the New York Times. Later that year, he spoke again of his new tool in another interview for American Magazine with Franklin Smith, and did speak of an innovation of his own in regard to it: "...Perfect as the instrument is, it has one disadvantage. After working the bellows all day, the hand of the artist becomes very tired, if not almost paralyzed. To overcome this difficulty, Mr. Fosdick has devised in place of the bellows a compressed air chamber. By regulating the flow of the air, he obtains the same results as with the bellows."

Patty Thum's August 1894 letter to the editor of the Art Interchange was a response to J. Wm. Fosdick's 1894 article in their July issue. It appears from that 1894 letter to the editor that she thought the thermo-pyrography tool had been J. Wm. Fosdick's invention.

Now, in light of her 1891 letter to Charles Kurtz, it is even more astonishing to think that most probably Patty Thum invented her electric tool and wrote her 1891 letter and article to him completely unaware of the existence of Manuel-Perier's thermo-pyrography tool and even before Fosdick's use of Manuel-Perier's thermo-pyrography tool.

Following is the complete transcription of Patty Thum's letter along with her draft article to art promoter and family friend Charles Kurtz:

1309 First St.

Louisville Ky

July 16th 1891

Dear Mr. Kurtz,

Will you have published the enclosed article in any publication over which you have any controls? I will tell you about it. It was a discovery of mine. I wrote to the Art Amateur about it. They replied immediately to write an article and illustrate it for them. I was rather leisurely I admit for Mandeville was in Washington and I wanted him to make perfectly sure my shaky electric knowledge but they (the Amateurs) have never complained of my being slow about it and in a few weeks I sent it on to them with four large illustrations and charged them $40 for the whole affair.

Mr. Marks is in Europe and although they usually pay that much for that amount of drawing merely Mr. White the editor in charge writes me that $40 was entirely too much—couldn't think of definitely accepting or rejecting it until Mr. Marks comes back from Europe. In the mean time he is going to publish an article covering my ground in the July magazine. Now isn't that hard?

So I have written him to please either accept it at $40 or return it to me at once. When he does I will telegraph you, if you are willing and if he returns the article please have published the copy I send you in any thing that is atall a conspicious [sic] publication before the July Amateur can appear. If he pays the $40 I have bothered you in vain, but after his reply it will be too late to anticipate him except by telegraph so I send the enclosed to you now. Of course I would appreciate all the money I could get for it but what I principally want is revenge!

I will not have time to send any illustrations but it will do very well without.

This electric point-drawing is entirely new in this part of the country and little known I am sure any where for I have looked in vain for any publication bearing on it.

Mr. White says however that it has been known and been popular in England for about a year. At any rate it is novel enough to be passably interesting don't you think?

Do you mind doing this for me?

If you do, don't do it for in any case I am

Your grateful friend

Patty Thum

I am still contributing to the Art Amateur and intend to go on doing so, so don't have any thing hateful said about them in this connection. I magnify my own unimportant affairs to a very egotistical extent dont I!

P. T.

The transcription of Patty Thum's handwritten draft for an article, which she enclosed in her 1891 letter, follows below. Some of her text references (specifically on the history and scope of the art form in the introductory paragraph) suggest that she not only saw works by J. William Fosdick in St. Louis, as she stated, but also that she must have seen some catalogue reference or other signage at his St. Louis exhibition with some history of the art form.* This is because Fosdick's 1891 article in the Art Interchange (with some of that same information) was not published until the December issue of that year, nearly half a year after her letter to Charles Kurtz.

Burnt Wood Work.

The Art of burning designs upon wood is an old one. Since very early days it has been occasionally employed. There exists in Spain an old collection of burnt panels made by monks and in Germany and the Isle of Guernsey there are examples of this work.

The Japanese too have used burnt wood work in their decorations.

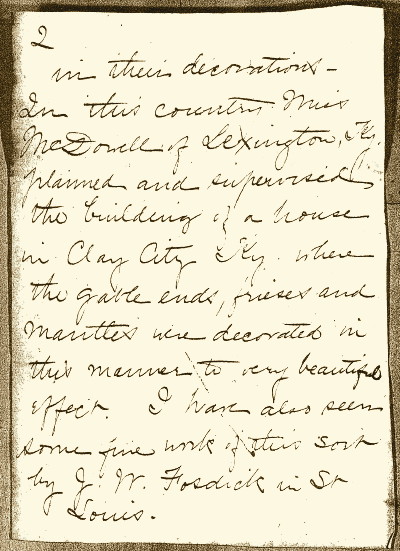

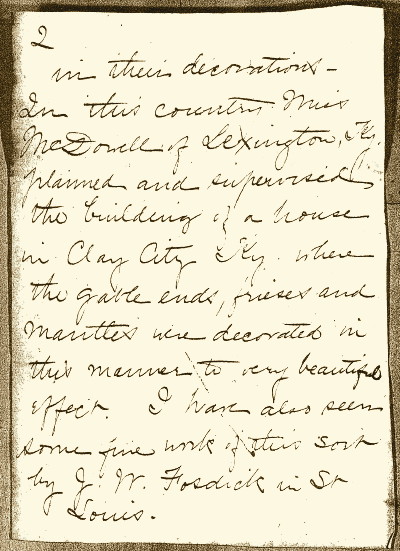

Burnt Wood Work article, page 2, dated July 1891.

In this country Miss McDowell of Lexington, Ky. planned and supervised the building of a house in Clay City Ky where the gable ends, frieses [sic] and mantles [sic] were decorated in this manner to very beautiful effect. I have also seen some fine work of this sort by J. W. Fosdick in St Louis.

But its possibilities for beauty and use have been so seldom thus developed that I think many are wholly unacquainted with them.

We have all seen "Poker Pictures" exhibited from time to time at expositions and county fairs along with watermelon seed landscapes, quilts made by aged ladies without glasses, portraits painted by boys of nine without instruction, and other works of art produced under disadvantageous circumstances of youth or age or paucity of material or tool. And so it has happened that burnt wood work has rather suffered in popular estimation, its great possibilities for beauty have passed unrecognized and adherements in that line have been considered curious triumphs over unwilling means.

And this view was justified somewhat when the troublesome nature of the tools was considered.

Irons heated in the fire that were at first too hot or too cool for exactly the shade the artist wished or that cooled to inert desuetude after he had made half a stroke were not a happy means of expression, were at times exasperating.

Any small fine lines were more difficult than the coarser ones owing to the greater quickness of the small points to cool. Almost before you remembered what you wished to do with it its heat had vanished.

But this can now be all changed by the intervention of electricity. The electric battery can heat to any desired degree a pointed platinum loop of any desired size and keep it at just the same heat. By a turn of the lever of the rheostat the current may be increased or diminished and the platinum point be at a white heat or a dull red glow and thus with a pencil of fire you can draw on and on as long as you wish.

The battery I have used is the Storage Battery number 30 in the catalogue of Wait and Bartlett Manufacturing Co. 143 East 23rd St. New York City. It is the second in size and with ten "crowfoot" jars to charge it answers the purpose adequately. The price of this battery is I think $75.

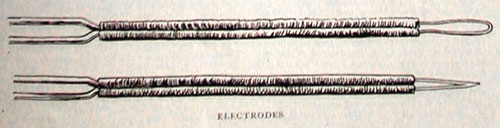

The advantage of a storage battery is the steadiness of the current obtainable. But also the electricity from an electric light wire can be used for this purpose by the interposition of a rheostat to regulate it. The points, or electrodes, I have used were not made for the purpose of drawing and might be improved upon

The point of the electrode that I have is too far off from the handle and in a few minutes the silk covered wires near the point where the fingers grasp it get heated to an uncomfortable, though not dangerous, degree. It might be better for this use if they were enclosed in some non-heat-conducting medium as the lead in the pencil is enclosed in wood. As it is I overcome the difficulty by wrapping paper around the electrode where I must hold it.

Care must be taken that the battery is not turned on too strong for there is danger in that case of the platinum wire being burnt out. And the draughsman [sic] must not press the fiery point against the wood so hard as to bend it, there is no need for any but the lightest touch.

Artist folk are very apt to look on anything in the nature of an improvement in their tools as partaking too much of the machine made. But the slightest inquiry into this new method shows that it is a most individual and artistic means of producing beauty. The draughsman [sic] has no mechanical process between him and his result. This fire etching can be more certain and as individual as acid etching. The fine gradations of tint from the natural hue of the wood, through the scorched surface, to the brown or black charred line are enough in the hands of knowledge for very decorative results. The absolute freedom of line not in any way dependent, as in wood carving upon the grain of the wood, make it much more expressive. On many surfaces where relief is undesirable it answers all the decorative effect of the most elaborate carving. The practical housekeeper will rejoice in that it gathers no dust. The weary can lean against the most decorated chair back of this sort and suffer no ill. For largeness of effect on cornice or ceiling it cannot be surpassed and the minute delicacy now possible to it is adapted to the decoration of small boxes, blotter covers, book cases, paper knives, every thing and anything that is made of wood.

In a separate microfilm reel, dedicated to undated correspondence, was found this following fragment from Patty Thum that seems an appropriate ending for her article:

"And this ornamentation will not impare their usefulness nor seem to do so. A covering of varnish renders this fire drawing practically imperishable."

Patty Thum highlights some important aspects of the pyrographic art form in her draft article. One thing she observes is that nearly everybody knows about woodburning in its most basic form. Her discovery of "fire drawing" (which she seems to have named that in order to make the distinction) is to note that the basic technique was rarely developed as an artistic technique, and the art form as such has gone unnoticed and unappreciated as a result. In that regard, not much has changed since 1891, it seems.

In her letter to Charles Kurtz, she indicates that ELECTRIC fire-drawing is unknown where she is. She does note, however, that Mr. White (the Art Amateur editor in charge in Mr. Montague Marks' absence) told her it was already known in England for about a year.

Research is underway to find out whether this was really the case, or whether Gleeson White, who had only arrived from his native England in 1890 to act as associate editor of the Art Amateur from 1891–92, was referring to the burgeoning of the amateur pyrography movement there in general, or whether he was saying that as a bargaining ploy.

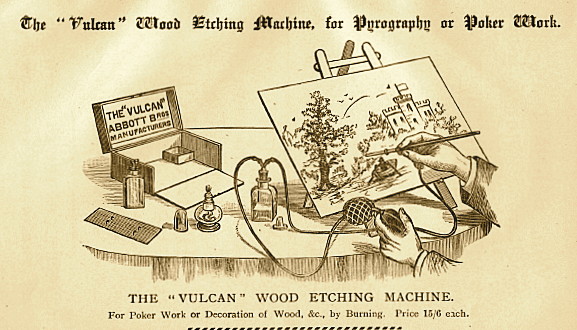

In England, the pyrotool made famous circa 1890 was the Vulcan tool featured in the book by Maud Maude; however, that tool was NOT ELECTRIC but a compact, practical version of Manuel-Perier's thermo-pyrography tool designed for the amateur market.

Louisville Ky

July 16th 1891

Will you have published the enclosed article in any publication over which you have any controls? I will tell you about it. It was a discovery of mine. I wrote to the Art Amateur about it. They replied immediately to write an article and illustrate it for them. I was rather leisurely I admit for Mandeville was in Washington and I wanted him to make perfectly sure my shaky electric knowledge but they (the Amateurs) have never complained of my being slow about it and in a few weeks I sent it on to them with four large illustrations and charged them $40 for the whole affair.

Mr. Marks is in Europe and although they usually pay that much for that amount of drawing merely Mr. White the editor in charge writes me that $40 was entirely too much—couldn't think of definitely accepting or rejecting it until Mr. Marks comes back from Europe. In the mean time he is going to publish an article covering my ground in the July magazine. Now isn't that hard?

So I have written him to please either accept it at $40 or return it to me at once. When he does I will telegraph you, if you are willing and if he returns the article please have published the copy I send you in any thing that is atall a conspicious [sic] publication before the July Amateur can appear. If he pays the $40 I have bothered you in vain, but after his reply it will be too late to anticipate him except by telegraph so I send the enclosed to you now. Of course I would appreciate all the money I could get for it but what I principally want is revenge!

I will not have time to send any illustrations but it will do very well without.

This electric point-drawing is entirely new in this part of the country and little known I am sure any where for I have looked in vain for any publication bearing on it.

Mr. White says however that it has been known and been popular in England for about a year. At any rate it is novel enough to be passably interesting don't you think?

Do you mind doing this for me?

If you do, don't do it for in any case I am

Patty Thum

But its possibilities for beauty and use have been so seldom thus developed that I think many are wholly unacquainted with them.

We have all seen "Poker Pictures" exhibited from time to time at expositions and county fairs along with watermelon seed landscapes, quilts made by aged ladies without glasses, portraits painted by boys of nine without instruction, and other works of art produced under disadvantageous circumstances of youth or age or paucity of material or tool. And so it has happened that burnt wood work has rather suffered in popular estimation, its great possibilities for beauty have passed unrecognized and adherements in that line have been considered curious triumphs over unwilling means.

And this view was justified somewhat when the troublesome nature of the tools was considered.

Irons heated in the fire that were at first too hot or too cool for exactly the shade the artist wished or that cooled to inert desuetude after he had made half a stroke were not a happy means of expression, were at times exasperating.

Any small fine lines were more difficult than the coarser ones owing to the greater quickness of the small points to cool. Almost before you remembered what you wished to do with it its heat had vanished.

But this can now be all changed by the intervention of electricity. The electric battery can heat to any desired degree a pointed platinum loop of any desired size and keep it at just the same heat. By a turn of the lever of the rheostat the current may be increased or diminished and the platinum point be at a white heat or a dull red glow and thus with a pencil of fire you can draw on and on as long as you wish.

The battery I have used is the Storage Battery number 30 in the catalogue of Wait and Bartlett Manufacturing Co. 143 East 23rd St. New York City. It is the second in size and with ten "crowfoot" jars to charge it answers the purpose adequately. The price of this battery is I think $75.

The advantage of a storage battery is the steadiness of the current obtainable. But also the electricity from an electric light wire can be used for this purpose by the interposition of a rheostat to regulate it. The points, or electrodes, I have used were not made for the purpose of drawing and might be improved upon

The point of the electrode that I have is too far off from the handle and in a few minutes the silk covered wires near the point where the fingers grasp it get heated to an uncomfortable, though not dangerous, degree. It might be better for this use if they were enclosed in some non-heat-conducting medium as the lead in the pencil is enclosed in wood. As it is I overcome the difficulty by wrapping paper around the electrode where I must hold it.

Care must be taken that the battery is not turned on too strong for there is danger in that case of the platinum wire being burnt out. And the draughsman [sic] must not press the fiery point against the wood so hard as to bend it, there is no need for any but the lightest touch.

Artist folk are very apt to look on anything in the nature of an improvement in their tools as partaking too much of the machine made. But the slightest inquiry into this new method shows that it is a most individual and artistic means of producing beauty. The draughsman [sic] has no mechanical process between him and his result. This fire etching can be more certain and as individual as acid etching. The fine gradations of tint from the natural hue of the wood, through the scorched surface, to the brown or black charred line are enough in the hands of knowledge for very decorative results. The absolute freedom of line not in any way dependent, as in wood carving upon the grain of the wood, make it much more expressive. On many surfaces where relief is undesirable it answers all the decorative effect of the most elaborate carving. The practical housekeeper will rejoice in that it gathers no dust. The weary can lean against the most decorated chair back of this sort and suffer no ill. For largeness of effect on cornice or ceiling it cannot be surpassed and the minute delicacy now possible to it is adapted to the decoration of small boxes, blotter covers, book cases, paper knives, every thing and anything that is made of wood.

|

|

The VULCAN Wood Etching Machine Illustrated in the book A Handbook on Pyrography or Burnt Wood Etching by Maud Maude, 1891. |

The discovery of Patty Thum's 1891 letter to Chas. Kurtz sheds a new light on the sequence of events regarding her invention of the electric pyrography tool with platinum wire tips. For one thing, the two drawings she submitted in her 1894 letter to the editor of Art Interchange (shown again below) now seem more likely to date from 1891 when she submitted her original article to the Art Amateur with four illustrations and had asked for them back when Gleeson White rejected them.

It is also looking as though her original article was not published anywhere else after that—neither the formal one with the four illustrations she submitted to the Art Amateur nor the draft she sent to Chas. Kurtz without them.** The fact that she was willing to submit two drawings in 1894 to Art Interchange as part of a (presumably unremunerated) letter to the editor rather than a (paid) article suggests that she had no further use for the drawings and that this was a last effort. There is no evidence thus far to indicate that her tool was commercialized once she introduced it.

A cryptic follow-up letter, however, sent only six days after her July 16th one, instead of shedding more light on the events, only lends itself to more confusion over the final outcome regarding her submission to the Art Amateur. Her 1891 letter of July 22nd to Chas. Kurtz began as follows: "Just after I sent that second letter Mr. Stephenson was in Louisville and told us of your being in Europe. I was immediately accutely [sic] sorry I had bothered you with that burnt wood work. I hoped that it would not be forwarded to you and that its two cent stamp would keep it from wandering so far. Please burn it up as I do not need it any more. Thank you very much for Mr. Marks addresses...."

It seems that fate stepped in and this admirable innovation of hers was lost to the world. Over the next couple of decades or so, the thermo-pyrography tool was the one manufactured/distributed by many companies in different countries, and pyrography became an enormously popular hobby for many amateurs around the world. Patty Thum's invention was a quarter century ahead of its time and was never, it seems, to be recognized in her lifetime.

The E-Museum is still hopeful that pyrography works by Patty Thum may come to light and that her unique electric pyrography tool*** may yet be discovered.

| ||

Patty Thum's Electric Pyrography Tool

Electrodes—Platinum Wire Tips | Drawings by Patty Prather Thum, circa 1891 Published in The Art Interchange in September 1894 as a response to their July 1894 article by J. William Fosdick Digital image by Sharon H. Garvey, ©2006 Article with images courtesy of Anna North Coit of the North Stonington Historical Society North Stonington, Connecticut, U.S.A. |

The transcription of an excerpt from her letter sent fully a month BEFORE the other two "ties up a few loose ends" and explains more fully how this whole event came to be.

1309 First St.

Louisville Ky

June 15th 1891

Dear Mr. Kurtz,

I begin with my usual tiresome cry—please do me another kindness.

This time I hope it will not give you much trouble. I want the address of Mr. Montague Marks who is now in Europe. Mr. Gleeson White who edits the magazine in his absence is such a bother and I want to write direct to Mr. Marks. Please if you ask at the office of the Art Amateur do not mention that you want it for me because it might offend Mr. White. This sounds very underhanded, but it isn't, its perfectly fair and square and I do not explain it all out here only for the reason that I do not want to bore you to death.

I hope you are all well. We are, and enjoying life in spite of the heat....

Remember me to all yours with affection.

Very truly,

Patty Thum

Louisville Ky

June 15th 1891

Dear Mr. Kurtz,

I begin with my usual tiresome cry—please do me another kindness.

This time I hope it will not give you much trouble. I want the address of Mr. Montague Marks who is now in Europe. Mr. Gleeson White who edits the magazine in his absence is such a bother and I want to write direct to Mr. Marks. Please if you ask at the office of the Art Amateur do not mention that you want it for me because it might offend Mr. White. This sounds very underhanded, but it isn't, its perfectly fair and square and I do not explain it all out here only for the reason that I do not want to bore you to death.

I hope you are all well. We are, and enjoying life in spite of the heat....

Remember me to all yours with affection.

Patty Thum

* UPDATE—25 September 2008: Additional research has uncovered an 1889 catalogue of the St. Louis Exhibition of Decorative Burnt Wood by J. William Fosdick, which adds one more piece of information to the Patty Thum Mystery.

** UPDATE—18 September 2008: Further research has uncovered a September 1891 article—not by Patty Thum but by Emma Haywood—entitled Pyrography, or Burnt Wood Etching, which adds a new twist to the Patty Thum Mystery.

*** UPDATE—11 October 2008: A reference at the beginning of Emma Haywood's September 1891 article has lead to a December 1888 article entitled The Use of Charred Wood in Interior Decoration, which surprisingly quotes J. William Fosdick at that early date mentioning a platinum wire tip heated by an electric current.

*** UPDATE—27 October 2009: A 1909 article by J. William Fosdick, entitled The Art of Fire-Etching, talks for the first time of his own experimentation with an electric pyrography tool. This article also gives us a new date for his first use of the thermo-pyrography tool; in addition, he attributes its invention to Germany rather than France.

*** UPDATE—11 October 2008: A reference at the beginning of Emma Haywood's September 1891 article has lead to a December 1888 article entitled The Use of Charred Wood in Interior Decoration, which surprisingly quotes J. William Fosdick at that early date mentioning a platinum wire tip heated by an electric current.

*** UPDATE—27 October 2009: A 1909 article by J. William Fosdick, entitled The Art of Fire-Etching, talks for the first time of his own experimentation with an electric pyrography tool. This article also gives us a new date for his first use of the thermo-pyrography tool; in addition, he attributes its invention to Germany rather than France.

= = = N O T I C E = = =

On November 1st, 2009, a special exhibition of the works of Victorian artist Patty Thum opened at the Howard Steamboat Museum

in Jeffersonville, Indiana.

Her pyrography story on exhibit here in the E-Museum opens a new area of interest in Patty Thum's life and works, and is likewise a call to anyone who may have examples of her pyrography or her unique electric pyrography tool to please come forward.

If you have either any questions to ask or any information to offer regarding this letter to Charles Kurtz from Patty Thum, any works in "fire drawing" by her, or the remarkable electric pyrography tool that, by her own account, she invented in about 1891, please e-mail the E-Museum Curator.

You are leaving the Salon of

Patty Thum's 1891 Letter to Charles Kurtz

Describing Her Discovery of "Fire Drawing"

and Her Invention of an Electric Pyrography Tool with Wire Tips

You can return to the

Patty Thum 1894 Salon,

the Pyrography Tools and Techniques Exhibit,

the Antique Art Hall,

or continue on your tour to one of the following

Pyrographic Art Exhibit Halls:

Portraits and Paintings

Decorative and Applied Art

Sculpture

Folk and Traditional Art

Children's Pyrographic Art

Special Pyrographic Art

The Book Store and E-Museum Library exhibits

Pyrographic Tools and Techniques exhibit

Your questions and comments are welcome and appreciated. Please e-mail the E-Museum Curator.

Back to E-Museum Entrance homepage

© 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011 Kathleen M. Garvey Menéndez, all rights reserved

Last updated 4 February 2011.